“How does depth help?” is a fundamental question in the theory of deep learning. Conventional wisdom, backed by theoretical studies (e.g. Eldan & Shamir 2016; Raghu et al. 2017; Lee et al. 2017; Cohen et al. 2016; Daniely 2017; Arora et al. 2018), holds that adding layers increases expressive power. But often this expressive gain comes at a price –optimization is harder for deeper networks (viz., vanishing/exploding gradients). Recent works on “landscape characterization” implicitly adopt this worldview (e.g. Kawaguchi 2016; Hardt & Ma 2017; Choromanska et al. 2015; Haeffele & Vidal 2017; Soudry & Carmon 2016; Safran & Shamir 2017). They prove theorems about local minima and/or saddle points in the objective of a deep network, while implicitly assuming that the ideal landscape would be convex (single global minimum, no other critical point). My new paper with Sanjeev Arora and Elad Hazan makes the counterintuitive suggestion that sometimes, increasing depth can accelerate optimization.

Our work can also be seen as one more piece of evidence for a nascent belief that overparameterization of deep nets may be a good thing. By contrast, classical statistics discourages training a model with more parameters than necessary as this can lead to overfitting.

$\ell_p$ Regression

Let’s begin by considering a very simple learning problem - scalar linear regression with $\ell_p$ loss (our theory and experiments will apply to $p>2$):

\[\min_{\mathbf{w}}~L(\mathbf{w}):=\frac{1}{p}\sum_{(\mathbf{x},y)\in{S}}(\mathbf{x}^\top\mathbf{w}-y)^p\]$S$ here stands for a training set, consisting of pairs $(\mathbf{x},y)$ where $\mathbf{x}$ is a vector representing an instance and $y$ is a (numeric) scalar standing for its label; $\mathbf{w}$ is the parameter vector we wish to learn. Let’s convert the linear model to an extremely simple “depth-2 network”, by replacing the vector $\mathbf{w}$ with a vector $\mathbf{w_1}$ times a scalar $\omega_2$. Clearly, this is an overparameterization that does not change expressiveness, but yields the (non-convex) objective:

\[\min_{\mathbf{w_1},\omega_2}~L(\mathbf{w_1},\omega_2):=\frac{1}{p}\sum_{(\mathbf{x},y)\in{S}}(\mathbf{x}^\top\mathbf{w_1}\omega_2-y)^p\]We show in the paper, that if one applies gradient descent over $\mathbf{w_1}$ and $\omega_2$, with small learning rate and near-zero initialization (as customary in deep learning), the induced dynamics on the overall (end-to-end) model $\mathbf{w}=\mathbf{w_1}\omega_2$ can be written as follows:

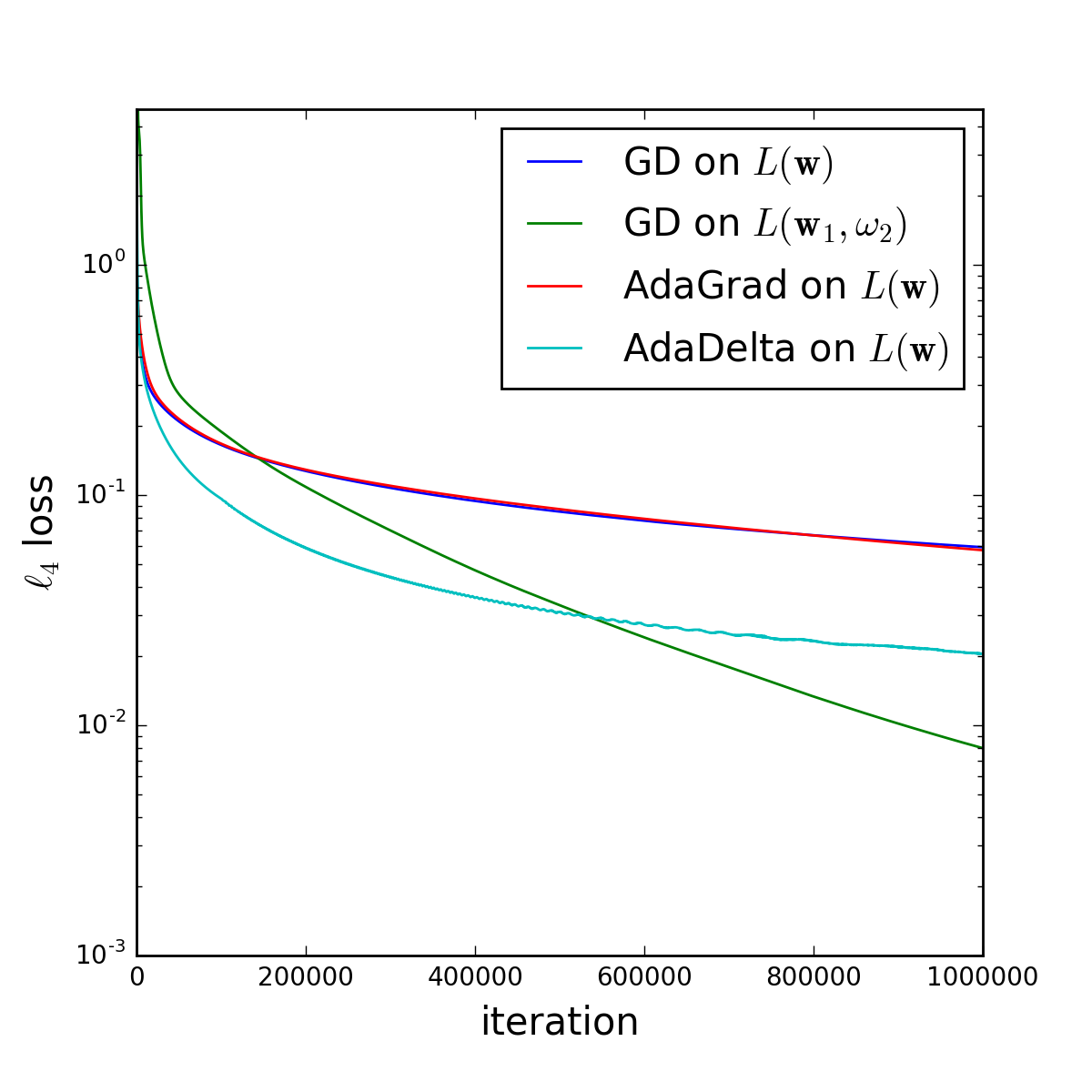

\[\mathbf{w}^{(t+1)}\leftarrow\mathbf{w}^{(t)}-\rho^{(t)}\nabla{L}(\mathbf{w}^{(t)})-\sum_{\tau=1}^{t-1}\mu^{(t,\tau)}\nabla{L}(\mathbf{w}^{(\tau)})\]where $\rho^{(t)}$ and $\mu^{(t,\tau)}$ are appropriately defined (time-dependent) coefficients. Thus the seemingly benign addition of a single multiplicative scalar turned plain gradient descent into a scheme that somehow has a memory of past gradients —the key feature of momentum methods— as well as a time-varying learning rate. While theoretical analysis of the precise benefit of momentum methods is never easy, a simple experiment with $p=4$, on UCI Machine Learning Repository’s “Gas Sensor Array Drift at Different Concentrations” dataset, shows the following effect:

Not only did the overparameterization accelerate gradient descent, but it has done so more than two well-known, explicitly designed acceleration methods – AdaGrad and AdaDelta (the former did not really provide a speedup in this experiment). We observed similar speedups in other settings as well.

What is happening here? Can non-convex objectives corresponding to deep networks be easier to optimize than convex ones? Is this phenomenon common or is it limited to toy problems as above? We take a first crack at addressing these questions…

Overparameterization: Decoupling Optimization from Expressiveness

A general study of the effect of depth on optimization entails an inherent difficulty - deeper networks may seem to converge faster due to their superior expressiveness. In other words, if optimization of a deep network progresses more rapidly than that of a shallow one, it may not be obvious whether this is a result of a true acceleration phenomenon, or simply a byproduct of the fact that the shallow model cannot reach the same loss as the deep one. We resolve this conundrum by focusing on models whose representational capacity is oblivious to depth - linear neural networks, the subject of many recent studies. With linear networks, adding layers does not alter expressiveness; it manifests itself only in the replacement of a matrix parameter by a product of matrices - an overparameterization. Accordingly, if this leads to accelerated convergence, one can be certain that it is not an outcome of any phenomenon other than favorable properties of depth for optimization.

Implicit Dynamics of Depth

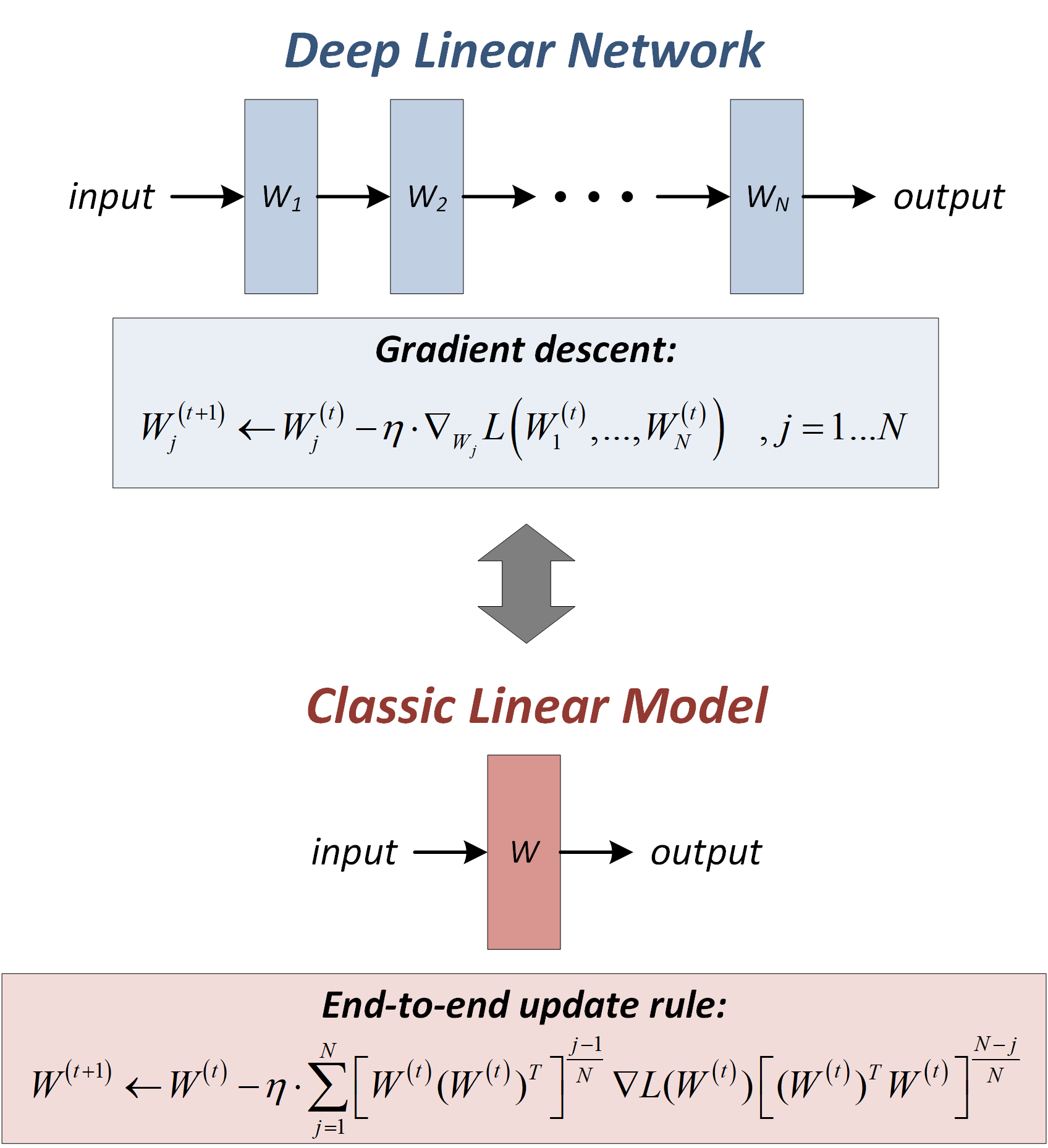

Suppose we are interested in learning a linear model parameterized by a matrix $W$, through minimization of some training loss $L(W)$. Instead of working directly with $W$, we replace it by a depth $N$ linear neural network, i.e. we overparameterize it as $W=W_{N}W_{N-1}\cdots{W_1}$, with $W_j$ being weight matrices of individual layers. In the paper we show that if one applies gradient descent over $W_{1}\ldots{W}_N$, with small learning rate $\eta$, and with the condition:

\[W_{j+1}^\top W_{j+1} = W_j W_j^\top\]satisfied at optimization commencement (note that this approximately holds with standard near-zero initialization), the dynamics induced on the overall end-to-end mapping $W$ can be written as follows:

\[W^{(t+1)}\leftarrow{W}^{(t)}-\eta\sum_{j=1}^{N}\left[W^{(t)}(W^{(t)})^\top\right]^\frac{j-1}{N}\nabla{L}(W^{(t)})\left[(W^{(t)})^\top{W}^{(t)}\right]^\frac{N-j}{N}\]We validate empirically that this analytically derived update rule (over classic linear model) indeed complies with deep network optimization, and take a series of steps to theoretically interpret it. We find that the transformation applied to the gradient $\nabla{L}(W)$ (multiplication from the left by $[WW^\top]^\frac{j-1}{N}$, and from the right by $[W^\top{W}]^\frac{N-j}{N}$, followed by summation over $j$) is a particular preconditioning scheme, that promotes movement along directions already taken by optimization. More concretely, the preconditioning can be seen as a combination of two elements:

- an adaptive learning rate that increases step sizes away from initialization; and

- a “momentum-like” operation that stretches the gradient along the azimuth taken so far.

An important point to make is that the update rule above, referred to hereafter as the end-to-end update rule, does not depend on widths of hidden layers in the linear neural network, only on its depth ($N$). This implies that from an optimization perspective, overparameterizing using wide or narrow networks has the same effect - it is only the number of layers that matters. Therefore, acceleration by depth need not be computationally demanding - a fact we clearly observe in our experiments (previous figure for example shows acceleration by orders of magnitude at the price of a single extra scalar parameter).

Beyond Regularization

The end-to-end update rule defines an optimization scheme whose steps are a function of the gradient $\nabla{L}(W)$ and the parameter $W$. As opposed to many acceleration methods (e.g. momentum or Adam) that explicitly maintain auxiliary variables, this scheme is memoryless, and by definition born from gradient descent over something (overparameterized objective). It is therefore natural to ask if we can represent the end-to-end update rule as gradient descent over some regularization of the loss $L(W)$, i.e. over some function of $W$. We prove, somewhat surprisingly, that the answer is almost always negative - as long as the loss $L(W)$ does not have a critical point at $W=0$, the end-to-end update rule, i.e. the effect of overparameterization, cannot be attained via any regularizer.

Acceleration

So far, we analyzed the effect of depth (in the form of overparameterization) on optimization by presenting an equivalent preconditioning scheme and discussing some of its properties. We have not, however, provided any theoretical evidence in support of acceleration (faster convergence) resulting from this scheme. Full characterization of the scenarios in which there is a speedup goes beyond the scope of our paper. Nonetheless, we do analyze a simple $\ell_p$ regression problem, and find that whether or not increasing depth accelerates depends on the choice of $p$: for $p=2$ (square loss) adding layers does not lead to a speedup (in accordance with previous findings by Saxe et al. 2014); for $p>2$ it can, and this may be attributed to the preconditioning scheme’s ability to handle large plateaus in the objective landscape. A number of experiments, with $p$ equal to 2 and 4, and depths ranging between 1 (classic linear model) and 8, support this conclusion.

Non-Linear Experiment

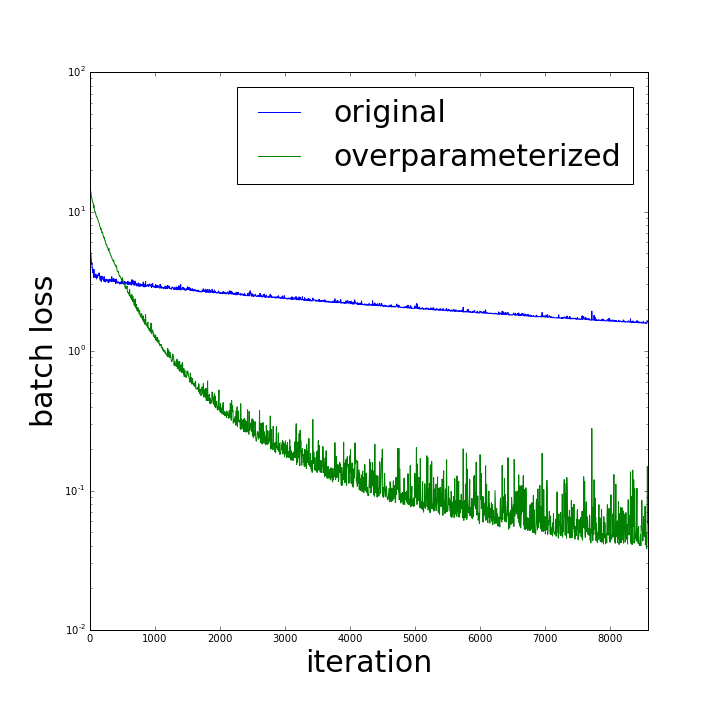

As a final test, we evaluated the effect of overparameterization on optimization in a non-idealized (yet simple) deep learning setting - the convolutional network tutorial for MNIST built into TensorFlow. We introduced overparameterization by simply placing two matrices in succession instead of the matrix in each dense layer. With an addition of roughly 15% in number of parameters, optimization accelerated by orders of magnitude:

We note that similar experiments on other convolutional networks also gave rise to a speedup, but not nearly as prominent as the above. Empirical characterization of conditions under which overparameterization accelerates optimization in non-linear settings is potentially an interesting direction for future research.

Conclusion

Our work provides insight into benefits of depth in the form of overparameterization, from the perspective of optimization. Many open questions and problems remain. For example, is it possible to rigorously analyze the acceleration effect of the end-to-end update rule (analogously to, say, Nesterov 1983 or Duchi et al. 2011)? Treatment of non-linear deep networks is of course also of interest, as well as more extensive empirical evaluation.