The ability of large neural networks to generalize is commonly believed to stem from an implicit regularization — a tendency of gradient-based optimization towards predictors of low complexity. A lot of effort has gone into theoretically formalizing this intuition. Tackling modern neural networks head-on can be quite difficult, so existing analyses often focus on simplified models as stepping stones. Among these, matrix and tensor factorizations have attracted significant attention due to their correspondence to linear neural networks and certain shallow non-linear convolutional networks, respectively. Specifically, they were shown to exhibit an implicit tendency towards low matrix and tensor ranks, respectively.

This post overviews a recent ICML 2022 paper with Asaf Maman and Nadav Cohen, in which we draw closer to practical deep learning by analyzing hierarchical tensor factorization, a model equivalent to certain deep non-linear convolutional networks. We find that, analogously to matrix and tensor factorizations, the implicit regularization in hierarchical tensor factorization strives to lower a notion of rank (called hierarchical tensor rank). This turns out to have surprising implications on the origin of locality in convolutional networks, inspiring a practical method (explicit regularization scheme) for improving their performance on tasks with long-range dependencies.

Background: Matrix and Tensor Factorizations

To put our work into context, let us briefly go over existing dynamical characterizations of implicit regularization in matrix and tensor factorizations. In both cases they suggest an incremental learning process that leads to low rank solutions (for respective notions of rank). We will then see how these characterizations transfer to the considerably richer hierarchical tensor factorization.

Matrix factorization: Incremental matrix rank learning

Matrix factorization is arguably the most extensively studied model in the context of implicit regularization. Indeed, it was already discussed in four previous posts (1, 2, 3, 4), but for completeness we will present it once more. Consider the task of minimizing a loss $\mathcal{L}_M : \mathbb{R}^{D, D’} \to \mathbb{R}$ over matrices, e.g. $\mathcal{L}_M$ can be a matrix completion loss — mean squared error over observed entries from some ground truth matrix. Matrix factorization refers to parameterizing the solution $W_M \in \mathbb{R}^{D, D’}$ as a product of $L$ matrices, and minimizing the resulting objective using gradient descent (GD):

Essentially, matrix factorization amounts to applying a linear neural network (fully connected neural network with no non-linearity) for minimizing $\mathcal{L}_M$. We can explicitly constrain the matrix rank of $W_M$ by limiting the shared dimensions of the weight matrices $\{ W^{(l)} \}_l$. However, from an implicit regularization standpoint, the most interesting case is where rank is unconstrained. In this case there is no explicit regularization, and the kind of solution we get is determined implicitly by the parameterization and the optimization algorithm.

Although it was initially conjectured that GD (with small initialization and step size) over matrix factorization minimizes a norm (see the seminal work of Gunasekar et al. 2017), recent evidence points towards an implicit matrix rank minimization (see Arora et al. 2019; Gidel et al. 2019; Razin & Cohen 2020; Chou et al. 2020; Li et al. 2021). In particular, Arora et al. 2019 characterized the dynamics of $W_M$’s singular values throughout optimization:

Theorem (informal; Arora et al. 2019): Gradient flow (GD with infinitesimal step size) over matrix factorization initialized near zero leads the $r$’th singular value of $W_M$, denoted $\sigma_M^{(r)} (t)$, to evolve by: [ \color{brown}{\frac{d}{dt} \sigma_M^{(r)} (t) \propto \sigma_M^{(r)} (t)^{2 - 2/L}} ~. ]

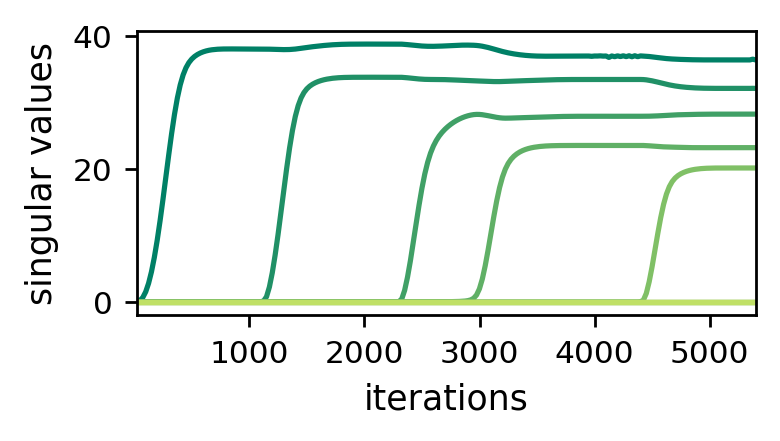

As can be seen from the theorem above, singular values evolve at a rate proportional to their size exponentiated by $2 - 2 / L$. This means that they are subject to a momentum-like effect, by which they move slower when small and faster when large. When initializing near the origin (as commonly done in practice), we therefore expect singular values to progress slowly at first, and then, upon reaching a certain threshold, to quickly rise until convergence. These dynamics create an incremental learning process that promotes solutions with few large singular values and many small ones, i.e. low matrix rank solutions. In their paper, Arora et al. 2019 support this qualitative explanation through theoretical illustrations and empirical evaluations. For example, the following plot reproduces one of their experiments:

Figure 1: Dynamics of singular values during GD over matrix factorization

— incremental learning leads to low matrix rank.

We note that the incremental matrix rank learning phenomenon was later on used to prove exact matrix rank minimization, under certain technical conditions (Li et al. 2021).

Tensor factorization: Incremental tensor rank learning

Despite the significant interest in matrix factorization, as a theoretical surrogate for deep learning its practical relevance is rather limited. It corresponds to linear neural networks, and thus misses non-linearity — a crucial aspect of modern neural networks. As was mentioned in a previous post, by moving from matrix (two-dimensional array) to tensor (multi-dimensional array) factorizations it is possible to address this limitation.

A classical scheme for factorizing tensors, named CANDECOMP/PARAFAC (CP), parameterizes a tensor as a sum of outer products (for more details on this scheme, see this excellent survey). Given a loss $\mathcal{L}_T : \mathbb{R}^{D_1, \ldots, D_N} \to \mathbb{R}$ over $N$-dimensional tensors, e.g. $\mathcal{L}_T$ can be a tensor completion loss, we simply refer by tensor factorization to parameterizing the solution $\mathcal{W}_T \in \mathbb{R}^{D_1, \ldots, D_N}$ as a CP factorization, and minimizing the resulting objective via GD:

Each term $\mathbf{w}_r^{(1)} \otimes \cdots \otimes \mathbf{w}_r^{(N)}$ in the sum is called a component, and $\otimes$ stands for outer product. The concept of rank naturally extends from matrices to tensors. For a given tensor $\mathcal{W}$, its tensor rank is defined to be the minimal number of components (i.e. of outer product summands) $R$ required for CP parameterization to express it. Note that we can explicitly constrain the tensor rank of $\mathcal{W}_T$ by limiting the number of components $R$. But, since our interest lies in implicit regularization, we consider the case where $R$ is large enough for any tensor to be expressed.

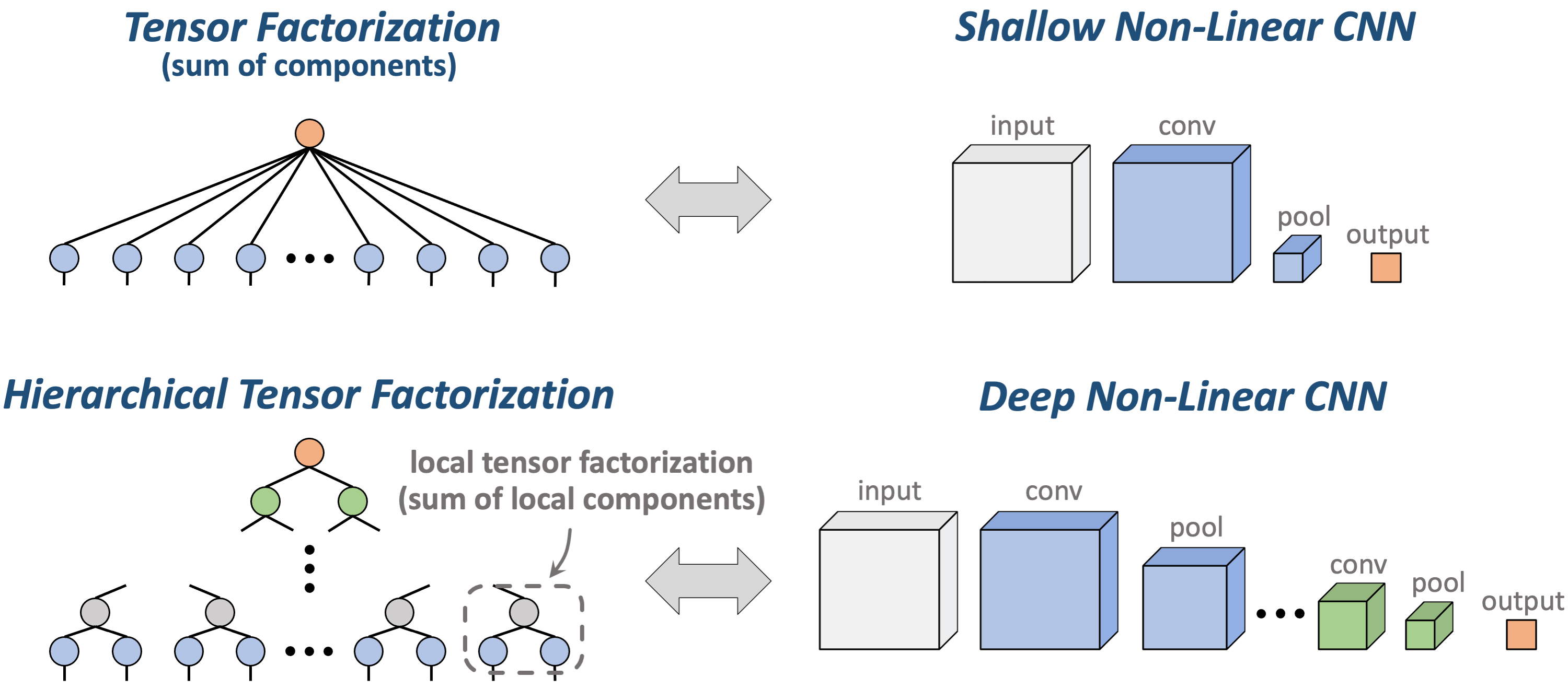

Similarly to how matrix factorization captures linear neural networks, tensor factorization is equivalent to certain shallow non-linear convolutional networks (with multiplicative non-linearity). This equivalence was discussed in a couple of previous posts (1, 2), for the exact details behind it feel free to check out the preliminaries section of our paper and references therein. The bottom line is that tensor factorization takes us one step closer to practical neural networks.

Motivated by the incremental learning dynamics in matrix factorization, in a previous paper (see accompanying blog post) we analyzed the behavior of component norms during optimization of tensor factorization:

Theorem (informal; Razin et al. 2021): Gradient flow over tensor factorization initialized near zero leads the $r$’th component norm, $\sigma_T^{(r)} (t) := || \mathbf{w}_r^1 (t) \otimes \cdots \otimes \mathbf{w}_r^N (t) ||$, to evolve by: [ \color{brown}{\frac{d}{dt} \sigma_T^{(r)} (t) \propto \sigma_T^{(r)} (t)^{2 - 2/N}} ~. ]

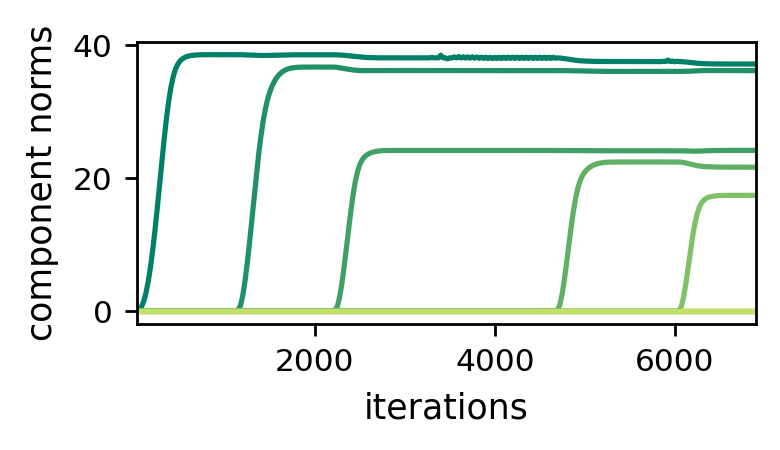

The dynamics of component norms in tensor factorization are structurally identical to those of singular values in matrix factorization. Accordingly, we get a momentum-like effect that attenuates the movement of small component norms and accelerates that of large ones. This suggests that, in analogy with matrix factorization, when initializing near zero components tend to be learned incrementally, resulting in a bias towards low tensor rank. The following plot empirically demonstrates this phenomenon:

Figure 2: Dynamics of component norms during GD over tensor factorization

— incremental learning leads to low tensor rank.

Continuing with the analogy to matrix factorization, the incremental tensor rank learning phenomenon formed the basis for proving exact tensor rank minimization, under certain technical conditions (Razin et al. 2021).

Hierarchical Tensor Factorization

Tensor factorization took us beyond linear predictors, yet it still lacks a critical feature of modern neural networks — depth (recall that it corresponds to shallow non-linear convolutional networks). A natural extension that accounts for both non-linearity and depth is hierarchical tensor factorization — our protagonist — which corresponds to certain deep non-linear convolutional networks (with multiplicative non-linearity). This equivalence is actually not new, and has facilitated numerous analyses of expressive power in deep learning (see this survey for a high-level overview).

As opposed to tensor factorization, which is a simple construct dating back to at least the early 20’th century (Hitchcock 1927), hierarchical tensor factorization was formally introduced only recently (Hackbusch & Kuhn 2009), and is much more elaborate. Its exact definition is rather technical (the interested reader can find it in our paper). For our current purpose it suffices to know that a hierarchical tensor factorization consists of multiple local tensor factorizations, whose components we call the local components of the hierarchical factorization.

Figure 3: Tensor factorization, which is a sum of components (outer products),

corresponds to a shallow non-linear convolutional neural network (CNN).

Hierarchical tensor factorization, which consists of multiple local tensor

factorizations, corresponds to a deep non-linear CNN.

In contrast to matrices, which have a single standard definition for rank, tensors posses several different definitions for rank.

Hierarchical tensor factorizations induce their own such notion, known as hierarchical tensor rank.

Basically, if a tensor can be represented through hierarchical tensor factorization with few local components, then it has low hierarchical tensor rank.

This stands in direct analogy with tensor rank, which is low if the tensor can be represented through tensor factorization with few components.

Seeing that the implicit regularization in matrix and tensor factorizations leads to low matrix and tensor ranks, respectively, in our paper we investigated whether the implicit regularization in hierarchical tensor factorization leads to low hierarchical tensor rank. That is, whether GD (with small initialization and step size) over hierarchical tensor factorization learns solutions that can be represented with few local components. Turns out it does.

Dynamical Analysis: Incremental Hierarchical Tensor Rank Learning

At the heart of our analysis is the following dynamical characterization for local component norms during optimization of hierarchical tensor factorization:

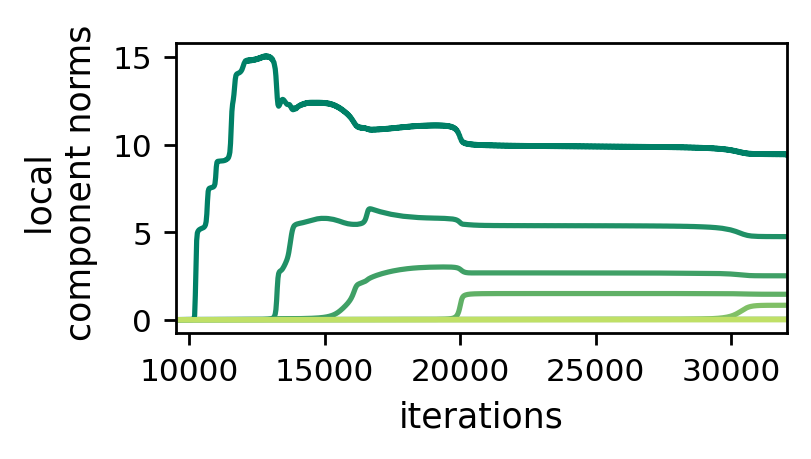

Theorem (informal): Gradient flow over hierarchical tensor factorization initialized near zero leads the $r$’th local component norm in a local tensor factorization, denoted $\sigma_H^{(r)} (t)$, to evolve by: [ \color{brown}{\frac{d}{dt} \sigma_H^{(r)} (t) \propto \sigma_H^{(r)} (t)^{2 - 2/K}} ~, ] where $K$ is the number of axes of the local tensor factorization.

This should really feel like deja vu, as these dynamics are structurally identical to those of singular values in matrix factorization and component norms in tensor factorization! Again, we have a momentum-like effect, by which local component norms move slower when small and faster when large. As a result, when initializing near zero local components tend to be learned incrementally, yielding a bias towards low hierarchical tensor rank. In the paper we provide theoretical and empirical demonstrations of this phenomenon. For example, the following plot shows the evolution of local component norms at some local tensor factorization under GD:

Figure 4: Dynamics of local component norms during GD over hierarchical

tensor factorization — incremental learning leads to low hierarchical tensor rank.

Practical Implication: Countering Locality in Convolutional Networks via Explicit Regularization

We saw that in hierarchical tensor factorization GD leads to solutions of low hierarchical tensor rank. But what does this even mean for the associated convolutional networks?

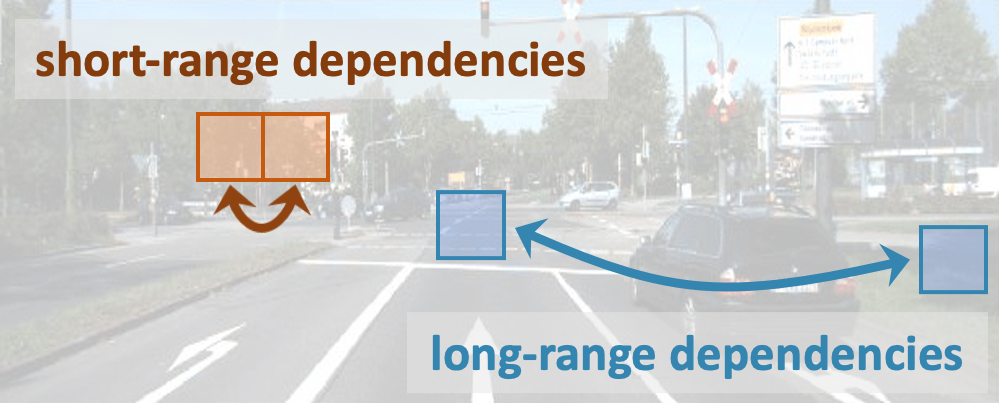

Hierarchical tensor rank is known (Cohen & Shashua 2017) to measure the strength of long-range dependencies modeled by a network. In the context of image classification, e.g., it quantifies how well we take into account dependencies between distant patches of pixels.

Figure 5: Illustration of short-range (local) vs. long-range dependencies in image data.

The implicit regularization towards low hierarchical tensor rank in hierarchical tensor factorization therefore translates to an implicit regularization towards locality in the corresponding convolutional networks.

At first this may not seem surprising, since convolutional networks typically struggle or completely fail to learn tasks entailing long-range dependencies.

However, conventional wisdom attributes this failure to expressive properties (i.e. to an inability of convolutional networks to realize functions modeling long-range dependencies), suggesting that addressing the problem requires modifying the architecture.

Our analysis, on the other hand, reveals that implicit regularization also plays a role: it is not just a matter of expressive power, the optimization algorithm is implicitly pushing towards local solutions.

Inspired by this observation, we asked:

Question: Is it possible to improve the performance of modern convolutional networks on long-range tasks via explicit regularization (without modifying their architecture)?

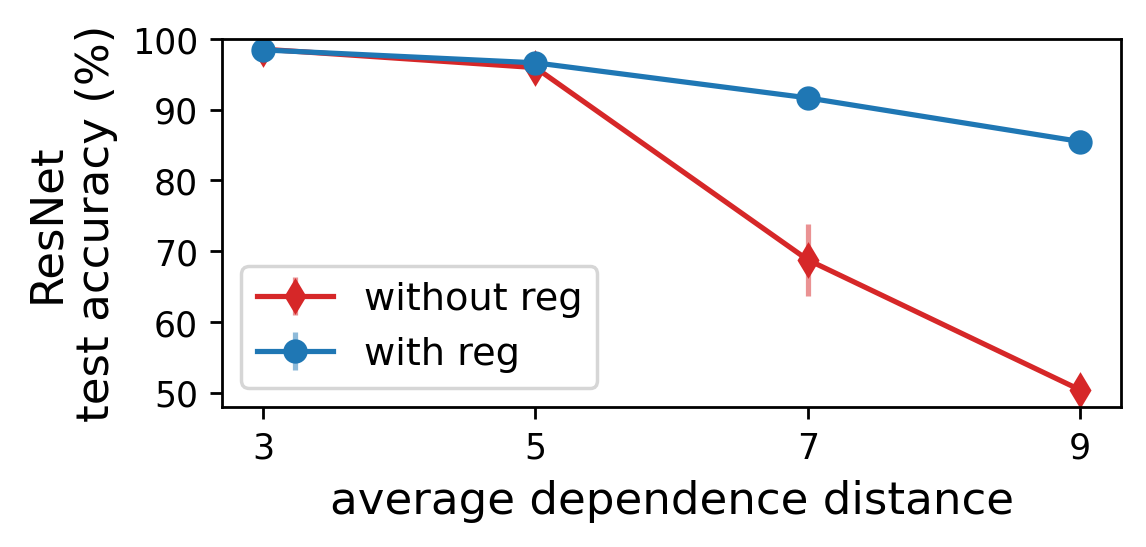

To explore this prospect, we designed explicit regularization that counteracts locality by promoting high hierarchical tensor rank (i.e. long-range dependencies). Then, through a series of controlled experiments, we confirmed that it can greatly improve the performance of modern convolutional networks (e.g. ResNets) on long-range tasks.

For example, the following plot displays test accuracies achieved by a ResNet on an image classification benchmark, in which it is possible to control the spatial range of dependencies required to model. When increasing the range of dependencies, the test accuracy obtained by an unregularized network substantially deteriorates, reaching performance no better than random guessing. As evident from the plot, our regularization closes the gap between short- and long-range tasks, significantly boosting generalization on the latter.

Figure 6: Specialized explicit regularization promoting high hierarchical tensor rank (i.e. long-range dependencies between image regions) can counter the locality of convolutional networks, significantly improving their performance on long-range tasks.

Concluding Thoughts

Looking forward, there are two main takeaways from our work:

-

Across three different neural network types (equivalent to matrix, tensor, and hierarchical tensor factorizations), we have an architecture-dependant notion of rank that is implicitly lowered. Moreover, the underlying mechanism for this implicit regularization is identical in all cases. This leads us to believe that implicit regularization towards low rank may be a general phenomenon. If true, finding notions of rank lowered for different architectures can facilitate an understanding of generalization in deep learning.

-

Our findings imply that the tendency of modern convolutional networks towards locality may largely be due to implicit regularization, and not an inherent limitation of expressive power as often believed. More broadly, they showcase that deep learning architectures considered suboptimal for certain tasks can be greatly improved through a right choice of explicit regularization. Theoretical understanding of implicit regularization may be key to discovering such regularizers.