Distributional methods for capturing meaning, such as word embeddings, often require observing many examples of words in context. But most humans can infer a reasonable meaning from very few or even a single occurrence. For instance, if we read “Porgies live in shallow temperate marine waters,” we have a good idea that a porgy is a fish. Since language corpora often have a long tail of “rare words,” it is an interesting problem to imbue NLP algorithms with this capability. This is especially important for n-grams (i.e., ordered n-tuples of words, like “ice cream”), many of which occur rarely in the corpus.

Here we describe a simple but principled approach called à la carte embeddings, described in our ACL’18 paper with Yingyu Liang, Tengyu Ma, and Brandon Stewart. It also easily extends to learning embeddings of arbitrary language features such as word-senses and $n$-grams. The paper also combines these with our recent deep-learning-free text embeddings to get simple deep-learning free text embeddings with even better performance on downstream classification tasks, quite competitive with deep learning approaches.

Inducing word embedding from their contexts: a surprising linear relationship

Suppose a single occurrence of a word $w$ is surrounded by a sequence $c$ of words. What is a reasonable guess for the word embedding $v_w$ of $w$? For convenience, we will let $u_w^c$ denote the average of the word embeddings of words in $c$. Anybody who knows the word2vec method may reasonably guess the following.

Guess 1: Up to scaling, $u_w^c$ is a good estimate for $v_w$.

Unfortunately, this totally fails. Even taking thousands of occurrences of $w$, the average of such estimates stays far from the ground truth embedding $v_w$. The following discovery should therefore be surprising (read below for a theoretical justification):

Theorem 1 (From this TACL’18 paper): There is a single matrix $A$ (depending only upon the text corpus) such that $A u_w^c$ is a good estimate for $v_w$.

Note that the best such $A$ can be found via linear regression by minimizing the average $|Au_w^c -v_w|^2$ over occurrences of frequent words $w$, for which we already have word embeddings.

Once such an $A$ has been learnt from frequent words, the induction of embeddings for new words works very well. As we receive more and more occurrences of $w$ the average of $Au_w^c$ over all sentences containing $w$ has cosine similarity $>0.9$ with the true word embedding $v_w$ (this holds for GloVe as well as word2vec).

Thus the learnt $A$ gives a way to induce embeddings for new words from a few or even a single occurrence. We call this the à la carte embedding of $w$, because we don’t need to pay the prix fixe of re-running GloVe or word2vec on the entire corpus each time a new word is needed.

Testing embeddings for rare words

Using Stanford’s Rare Words dataset we created the Contextual Rare Words dataset where, along with word pairs and human-rated scores, we also provide contexts (i.e., few usages) for the rare words.

We compare the performance of our method with alternatives such as top singular component removal and frequency down-weighting and find that à la carte embedding consistently outperforms other methods and requires far fewer contexts to match their best performance. Below we plot the increase in Spearman correlation with human ratings as the tested algorithms are given more samples of the words in context. We see that given only 8 occurences of the word, the a la carte method outperforms other baselines that’re given 128 occurences.

Now we turn to the task mentioned in the opening para of this post. Herbelot and Baroni constructed a “nonce” dataset consisting of single-word concepts and their Wikipedia definitions, to test algorithms that “simulate the process by which a competent speaker encounters a new word in known contexts.” They tested various methods, including a modified version of word2vec. As we show in the table below, à la carte embedding outperforms all their methods in terms of the average rank of the target vector’s similarity with the constructed vector. The true word embedding is among the closest 165 or so word vectors to our embedding. (Note that the vocabulary size exceeds 200K, so this is considered a strong performance.)

A theory of induced embeddings for general features

Why should the matrix $A$ mentioned above exist in the first place? Sanjeev, Yingyu, and Tengyu’s TACL’18 paper together with Yuanzhi Li and Andrej Risteski gives a justification via a latent-variable model of corpus generation that is a modification of their earlier model described in TACL’16 (see also this blog post) The basic idea is to consider a random walk over an ellipsoid instead of the unit square. Under this modification of the rand-walk model, whose approximate MLE objective is similar to that of GloVe, their first theorem shows the following:

\[\exists~A\in\mathbb{R}^{d\times d}\textrm{ s.t. }v_w=A\mathbb{E} \left[\frac{1}{n}\sum\limits_{w'\in c}v_{w'}\bigg|w\in c\right]=A\mathbb{E}v_w^\textrm{avg}~\forall~w\]where the expectation is taken over possible contexts $c$.

This result also explains the linear algebraic structure of the embeddings of polysemous words (words having multiple possible meanings, such as tie) discussed in an earlier post. Assuming for simplicity that $tie$ only has two meanings (clothing and game), it is easy to see that its word embedding is a linear transformation of the sum of the average context vectors of its two senses:

\[v_w=A\mathbb{E}v_w^\textrm{avg}=A\mathbb{E}\left[v_\textrm{clothing}^\textrm{avg}+v_\textrm{game}^\textrm{avg}\right]=A\mathbb{E}v_\textrm{clothing}^\textrm{avg}+A\mathbb{E}v_\textrm{game}^\textrm{avg}\]The above also shows that we can get a reasonable estimate for the vector of the sense clothing, and, by extension many other features of interest, by setting $v_\textrm{clothing}=A\mathbb{E}v_\textrm{clothing}^\textrm{avg}$. Note that this linear method also subsumes other context representations, such as removing the top singular component or down-weighting frequent directions.

$n$-gram embeddings

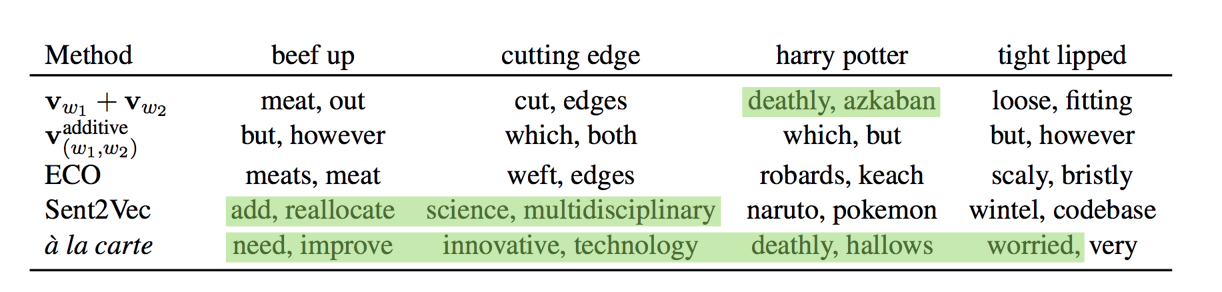

While the theory suggests existence of a linear transform between word embeddings and their context embeddings, one could also use this linear transform to induce embeddings for other kinds of linguistic features in context. We test this hypothesis by inducing embeddings for $n$-grams by using contexts from a large text corpus and word embeddings trained on the same corpus. A qualitative evaluation of the $n$-gram embeddings is done by finding the closest words to it in terms of cosine similarity between the embeddings. As evident from the below figure, à la carte bigram embeddings capture the meaning of the phrase better than some other compositional and learned bigram embeddings.

Sentence embeddings

We also use these $n$-gram embeddings to construct sentence embeddings, similarly to DisC embeddings, to evaluate on classification tasks. A sentence is embedded as the concatenation of sums of embeddings for $n$-gram in the sentence for use in downstream classification tasks. Using this simple approach we can match the performance of other linear and LSTM representations, even obtaining state-of-the-art results on some of them. Note that Logeswaran and Lee is a contemporary paper that uses deep nets.

Discussion

Our à la carte method is simple, almost elementary, and yet gives results competitive with many other feature embedding methods and also beats them in many cases. Can one do zero-shot learning of word embeddings, i.e. inducing embeddings for a words/features without any context? Character level methods such as fastText can do this and it is a good problem to incorporate character level information into the à la carte approach (the few things we tried didn’t work so far).

The à la carte code is available here, allowing you to re-create the results described.