This post can be seen as an introduction to how nonconvex problems arise naturally in practice, and also the relative ease with which they are often solved.

I will talk about word embeddings, a geometric way to capture the “meaning” of a word via a low-dimensional vector. They are useful in many tasks in Information Retrieval (IR) and Natural Language Processing (NLP), such as answering search queries or translating from one language to another.

You may wonder: how can a 300-dimensional vector capture the many nuances of word meaning? And what the heck does it mean to “capture meaning?”

Properties of Word Embeddings

A simple property of embeddings obtained by all the methods I’ll describe is cosine similarity: the similarity between two words (as rated by humans on a $[-1,1]$ scale) correlates with the cosine of the angle between their vectors. To give an example, the cosine for milk and cow may be $0.6$, whereas for milk and stone it may be $0.2$, which is roughly the similarity human subjects assign to them.

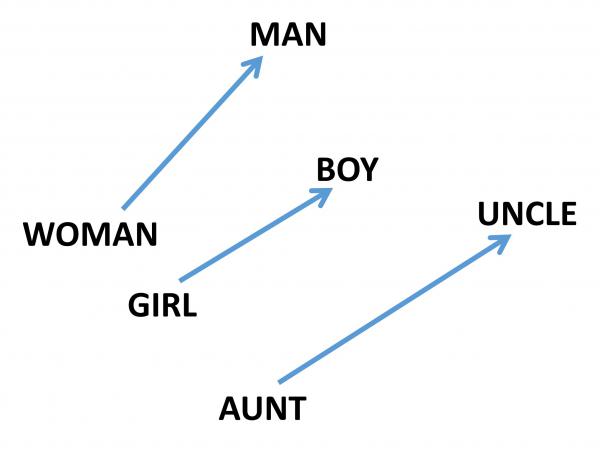

A more interesting property of recent embeddings is that they can solve analogy relationships via linear algebra. For example, the word analogy question man : woman ::king : ?? can be solved by looking for the word $w$ such that $v_{king} - v_w$ is most similar to $v_{man} - v_{woman}$; in other words, minimizes

\[||v_w - v_{king} + v_{man} - v_{woman}||^2.\]This simple idea can solve $75\%$ of analogy questions on some standard testbed. Note that the method is completely unsupervised: it constructs the embeddings using a big (unannotated) text corpus; and receives no training specific to analogy solving). Here is a rendering of this linear algebraic relationship between masculine-feminine pairs.

Good embeddings have other properties that will be covered in a future post. (Also, I can’t resist mentioning that fMRI-imaging of the brain suggests that word embeddings are related to how the human brain encodes meaning; see the well-known paper of Mitchell et al..)

Computing Word embeddings (via Firth’s Hypothesis)

In all methods, the word vector is a succinct representation of the distribution of other words around this word. That this suffices to capture meaning is asserted by Firth’s hypothesis from 1957, “You shall know a word by the company it keeps.” To give an example, if I ask you to think of a word that tends to co-occur with cow, drink, babies, calcium, you would immediately answer: milk.

Note that we don’t believe Firth’s hypothesis fully accounts for all aspects of semantics —understanding new metaphors or jokes, for example, seems to require other modes of experiencing the real world than simply reading text.

But Firth’s hypothesis does imply a very simple word embedding, albeit a very high-dimensional one.

Embedding 1: Suppose the dictionary has $N$ distinct words (in practice, $N =100,000$). Take a very large text corpus (e.g., Wikipedia) and let $Count_5(w_1, w_2)$ be the number of times $w_1$ and $w_2$ occur within a distance $5$ of each other in the corpus. Then the word embedding for a word $w$ is a vector of dimension $N$, with one coordinate for each dictionary word. The coordinate corresponding to word $w_2$ is $Count_5(w, w_2)$. (Variants of this method involve considering cooccurence of $w$ with various phrases or $n$-tuples.)

The obvious problem with Embedding 1 is that it uses extremely high-dimensional vectors. How can we compress them?

Embedding 2: Do dimension reduction by taking the rank-300 singular value decomposition (SVD) of the above vectors.

Recall that for an $N \times N$ matrix $M$ this means finding vectors $v_1, v_2, \ldots, v_N \in \mathbb{R}^{300}$ that minimize

\[\sum_{ij} (M_{ij} - v_i \cdot v_j)^2 \qquad (1).\]Using SVD to do dimension reduction seems an obvious idea these days but it actually is not. After all, it is unclear a priori why the above $N \times N$ matrix of cooccurance counts should be close to a rank-300 matrix. That this is the case was empirically discovered in the paper on Latent Semantic Indexing or LSI.

Empirically, the method can be improved by replacing the counts by their logarithm, as in Latent Semantic Analysis or LSA. Other authors claim square root is even better than logarithm. Another interesting empirical fact in the LSA paper is that dimension reduction via SVD not only compresses the embedding but improves its quality. (Improvement via compression is a familiar phenomenon in machine learning.) In fact they can use word vectors to solve word similarity tasks as well as the average American high schooler.

A research area called Vector Space Models (see survey by Turney and Pantel) studies various modifications of the above idea. Embeddings are also known to improve if we reweight the various terms in the above expression (2): popular reweightings include TF-IDF, PMI, Logarithm, etc.

Let me point out that reweighting the $(i, j)$ term in expression (1) leads to a weighted version of SVD, which is NP-hard. (I always emphasize to my students that a polynomial-time algorithm to compute rank-k SVD is a miracle, since modifying the problem statement in small ways makes it NP-hard.) But in practice, weighted SVD can be solved on a laptop in less than a day —remember, $N$ is rather large, about $10^5$!— by simple gradient descent on the objective (1), possibly also using a regularizer. (Of course, a lot has been proven about such gradient descent methods in context of convex optimization; the surprise is that they work also in such nonconvex settings.) Weighted SVD is a subcase of Matrix Factorization approaches in machine learning, which we will also encounter again in upcoming posts.

But returning to word embeddings, the following question had not been raised or debated, to the best of my knowledge: What property of human language explains the fact that these very high-dimensional matrices derived (in a nonlinear way) from word cooccurences are close to low-rank matrices? (In a future blog post I will describe our new theoretical explanation.)

The third embedding method I wish to describe uses energy-based models, for instance the Word2Vec family of methods from 2013 by the Google team of Mikolov et al., which also created a buzz due to the above-mentioned linear algebraic method to solve word analogy tasks. The word2vec models are inspired by pre-existing neural net models for language (basically, the word embedding corresponds to the neural net’s internal representation of the word; see this blog.). Let me describe the simplest variant, which assumes that the word vectors are related to word probabilities as follows:

Embedding 3 (Word2Vec(CBOW)):

\[\textstyle\Pr[w|w_1, w_2, \ldots, w_5] \propto \exp(v_w \cdot (\frac{1}{5} \sum_i v_{w_i})),\qquad (2)\]where the left hand side gives the empirical probability that word $w$ occurs in the text conditional on the last five words being $w_1$ through $w_5$.

Assume we can estimate the left hand side using a large text corpus. Then expression (2) for the word vectors—together with a constraint capping the dimension of the vectors to, say, 300 — implicitly defines a nonconvex optimization problem which is solved in practice as follows. Let $S$ be the set of all the $6$-tuples of words that occur in the text. Let $N$ be a set of random $6$-tuples; this set is called the negative sample since presumably these tuples are gibberish. The method consists of finding word embeddings that give high probability to tuples in $S$ and low probability to tuples in $N$. Roughly speaking, they maximise the difference between the following two quantities: (i) sum of $\exp(v_w \cdot (\frac{1}{5} \sum_i v_{w_i}))$ (suitably scaled) over all $6$-tuples in $S$, and (ii) the corresponding sum over tuples in $N$. The word2vec team introduced some other tweaks that allowed them to solve this optimization for very large corpora containing 10 billion words.

The word2vec papers are a bit mysterious, and have motivated much followup work. A paper by Levy and Goldberg (See Omer Levy’s Blog) explains that the word2vec methods are actually modern versions of older vector space methods. After all, if you take logs of both sides of expression (2), you see that the logarithm of some cooccurence probability is being expressed in terms of inner products of some word vectors, which is very much in the spirit of the older work. (Levy and Goldberg have more to say about this, backed up by interesting experiments comparing the vectors obtained by various approaches.)

Another paper by Pennington et al. at Stanford suggests a model called GLOVE that uses an explicit weighted-SVD strategy for finding word embeddings. They also give an intuitive explanation of why these embeddings solve word analogy tasks, though the explanation isn’t quite rigorous.

In a future post I will talk more about our subsequent theoretical work that tries to unify these different approaches, and also explains some cool linear algebraic properties of word embeddings. I note that linear structure also arises in representations of images learnt via deep learning., and it is tantalising to wonder if similar theory applies to that setting.